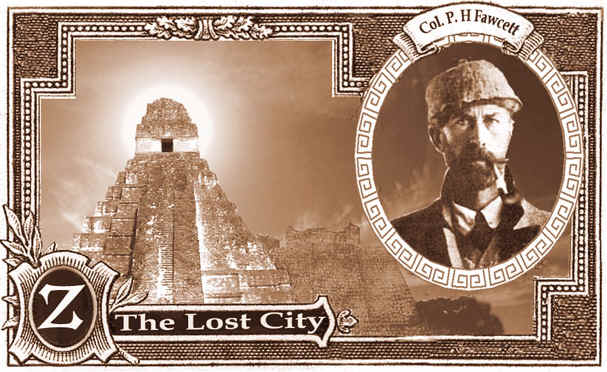

As an addendum to my review of the Southern Reach, here’s a great piece Jeff VanderMeer wrote expanding on his thoughts and reactions to David Grann’s The Lost City of Z, a nonfictional account of Victorian explorer Percy Fawcett’s obsession with and disappearance into the Amazon in search of a legendary ancient city. VanderMeer’s piece covers many of the same themes touched on in the Southern Reach, particularly the way our biases shape the limits of our understanding and the way our minds create patterns when confronted with randomness. Grann’s book itself seems an interesting thematic companion to VanderMeer’s trilogy, as a historical narrative of a place that eludes study, which is inexorably tangled with a person whose methods may be to blame.

Monthly Archives: March 2015

Mapping the Unknown Unknowns: Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach

Area X. It has a proper name―or it used to―but you aren’t allowed to know that. It’s to the south; don’t worry about where, exactly. You aren’t allowed to know that. It may be the future, or it may be the past, or it may be another world, or it may be a dream but―hey, you’re catching on!

There have been eleven expeditions. Officially. “Officially.” That may or may not be true―you aren’t allowed to know that. None of them came back; even the ones that went home didn’t come back. Not really. What came home weren’t really people: just outlines, like an image that’s been photocopied multiple times. They talked about how nice it was in Area X. Stressed how ordinary it was. Puzzled over the most mundane details like strangers to their own lives. Then they died―massive, unnaturally rapidly metastasizing systemic cancers. No meaningful information came back with them―they seemingly knew nothing.

Knowing less can protect you. This is one of the central ideas in Jeff VanderMeer’s latest, the alliteratively titled (in order: Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance) Southern Reach trilogy. VanderMeer is often compared to Lovecraft, and often responds to the comparison the way the child of a famous parent does, but the Southern Reach books are the first where I’ve recognized any family resemblance. Even leaving aside all the wonderful star-flung monsters (and there are many), “knowing less can protect you” sounds just like a coda of cosmicism, Lovecraft’s pessimistic philosophy which posits an indifferent universe where ultimate meaning is out of reach, and personal meaning is too small to matter. Lovecraft’s oeuvre is full of brave explorers who flew too close to the sun, ending ruined and mangled by the crippling cosmic knowledge they sought so desperately.

Rather than a paean to ignorance, this forms in Lovecraft a tragedy about the limits of human knowledge colliding with our need to know more (as well as a critique or lamentation of the cultural shift after the Industrial Revolution which began to seek meaning exclusively in the objective, where it always eludes us; but that’s a whole other subject). VanderMeer’s trilogy addresses the same premise, but slips out from underneath its constraints and goes off-script as soon as the reader looks away.

Initially, at the start of the first book, the reader knows as little as the narrator. We know none of the characters’ names. We’re given some sparse background information, but it’s safe to assume most of it is false. It’s safe to assume we know less than we know, already. This tone helps temper the initial disappointment that Area X is surprisingly mundane; whatever we had imagined before going in is so off-track we abruptly stop imagining and start watching uncritically. This is a neat trick, and mirrors how Tarkovsky introduces the Zone in Stalker, one of the books’ more obvious cousins. Our first contact with the lush, colorful Zone is so overwhelming it has a hypnotic paralysis after the bleakly industrial, monochrome world outside. Area X, also an uncanny garden ringed by the detritus of civilization, stuns by being so disquietingly unremarkable.

As the series goes on, the narrative perspective switches (from first, to third, to second person) to characters more and more deeply knowledgeable about and personally invested in Area X and the Southern Reach. This makes for a satisfying mystery, but each protagonist is successively more frustrated and impotent―the more they know, the more tangled up and incomplete their knowledge is and the less they’re able to comprehend. Meanwhile, the earlier, more ignorant, uncritical protagonists’ knowledge and comprehension expands at out of control rates. This is perhaps assisted by whatever entity or force is central to Area X (if there is an entity or force central to Area X); though they know nothing about Area X, Area X has some unique prior context for recognizing them.

It may be worth laying out one character’s given conditions for an Area X:

- a context we do not understand

- an attitude toward energy we do not understand

- an approach to language we do not understand

In other words, the oft-scoffed “unknown unknowns.” What we don’t know we don’t know; even guessing at the possible shapes in that murk are shots in the dark. Those conditions state little beyond: “We don’t know anything about what we don’t know we don’t know.”

If there’s a clear thread here, it’s that preconceptions poison genuine understanding: we are so in the habit of seeing what we look for that we don’t see what we look at. Throughout the series, a number of objects are presented to us with the implication that they are not what they appear to be. That isn’t a thistle―that’s only what you want to see. That isn’t a cell phone―that’s only what it means to you. This falls into a kind of general semantical science-fiction, recalling Korzybski’s, “Whatever this is, it is not a table!” and encouraging the reader to first question the presented reality, then to simply see it.

Coupled with this is recurring imagery of perfect mimicry, doppelgangers and simulacra. In Annihilation, the narrator notes that “pretending often leads to becoming a reasonable facsimile of what you mimic,” while her double in the second book becomes fixated on the idea of mimicry, and in the third abandons the idea of pretending to be “herself.” Environments and entities blend, disappear into one another, and the initially mundane appearance of Area X is revealed to be a facade we want to see.

Whether there is any substance underlying our preconceptions is left deliberately vague. Often what lies underneath a mask is another mask. This process of continual unmasking, infinite revelation, is perhaps the superior path to comprehension. Understanding may be acquired by letting go of the idea of absolute knowledge. Area X annihilates Aristotelian “either/or” thinking, can only be perceived through “both/and.” Our descriptions and preconceptions of what things should be obscures our vision of what they are. I’m not writing on a “keyboard.” You’re not reading on a “screen.” These don’t matter to, in fact hamper, comprehension.

A few brief notes on the physical formats of the books before moving on: they make excellent use of “blank” pages. The second is structured into sections following a creepy title scheme. Preceding each section is a “blank” page. Except they’re not blank—they’re shaded, and gradually darken as the mood becomes more oppressive. It’s a great, subtle way of affecting atmosphere. The third follows the same pattern in reverse, and manages to make that just as spooky. The dimensions of the copies here on my desk also do a fun thing. Authority is a half-inch shorter than its siblings. I don’t know if that’s deliberate, but it is cute.

One of many haunting images: a secret compartment containing journals and records. More journals and records than any of the various presented chronologies allow. An accumulation of too much knowledge, by too many people, left ritually abandoned. Knowledge beyond human capacity to process, and so perhaps best left out of human hands. From a recurring surreal passage, a sermon of sorts:

“…the shadows of the abyss are like the petals of a monstrous flower that shall blossom within the skull and expand beyond what any man can bear…”

We can only know so much. There isn’t room in that for knowing what we don’t know. There isn’t room enough even for comprehending all of what we do know. Reality is too vast and weird to fully take in. An ultimate picture always eludes us; there are always things in the margins of vision, often irrelevant to our experiences. Occasionally of fatal importance.

Reading these books, jotting notes here and there, and organizing my thoughts in writing has helped me reach a personal realization. I like weird fiction (and strangeness generally) because it often depicts a chaotic world, or a world whose order transcends mundane and human meaning. This has a stronger resonance with me than traditional science fiction or mainstream literature, which tend to depict highly ordered, sensible worlds, because my perception of life and the world fundamentally does not make sense. While I can take meaning from literary works exploring the human condition, I can’t get fully on board with something premised on life making sense; it doesn’t make sense. It’s nice to read literature that affirms that, and the Southern Reach trilogy perhaps reaches a little bit farther by presenting a universe that is chaotic, nonsensical, un-understandable―but comprehensible, so long as one stops clinging to rationality, ego, individuality. To sense. A conditional clause both chilling and beautiful.

You might have noticed how tight-lipped I’ve been about the more monstrous, mysterious, fantastical elements of the books. It’s not just an effort to avoid spoilers; it’s that discussing them isn’t conducive to understanding them. You have to see them for yourself.

In the end, it isn’t that there are things you’re not allowed to know, but that there are things you cannot know. Accepting this is the only way to overcome it. Pay attention to the immediate. Disappear into it. Expand throughout it. Become nothing; witness everything.